MOMA’s exhibition “Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light” is an exploration of an architect’s career little known except by architects.

The only things that keep West 53rd street from descending into a dense streetscape of banal skyscrapers which could be in Houston, Charlotte or La Defense are the exquisite American Folk Art Museum building and what remains of the original Museum of Modern Art. How does a museum that puts on the brilliantly curated and designed exhibit on an arcane French architect named Henri Labrouste announce at the same time their intention to demolish one of the most innovative pieces of architectural art in America?

A Blockbuster Named Labrouste

Although most of the expanded MOMA is little better than a mall for art, there are a few vignettes of brilliance.

The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) was created in 1929 by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (wife of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.) and two of her friends. Its first president, A. Conger Goodyear, was the former president of Buffalo’s Albright Art Gallery, often considered the first modern art museum in America. The Modern’s first permanent building was opened on West 53rd Street in 1939, designed in the International Style by Architects Phillip Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone. Philip Johnson redesigned the garden and was influential as both a design provocateur and a curator. Since 1983 the museum has expanded horizontally and vertically, first with the 53-story Museum Tower (mostly high priced residences) and in 2004 the expansion and redesign of the museum proper by Japanese architect Yoshio Taniguchi. Both the 1983 and 2004 expansions are boring and uninspired, dwarfing the gem-like original 1939 building and its neighbor, the American Folk Art Museum. MOMA in its 21st century form has become a mall for art.

Marcel Breuer’s “House in the Musuem Garden” was relocated to the Rockefeller estate, Kykuit, after the 1949 exhibition closed, and is now a scholar’s residence.

As trite as its recent architecture has been, the innovation of its curated exhibits and collecting has continued. These exhibits have both created global art phenomenon and recorded them including the 1932 groundbreaking International Exhibition of Modern Architecture curated by Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson whose accompanying book “The International Style” came to be the name of a global style; the 1949 “House in the Museum Garden” by Marcel Breuer; Arthur Drexler’s manifesto exhibition on “The Architecture of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts” in 1977; the introduction of an entire generation to Viennese Art, Architecture & Design in 1986 and now “Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light.”

How could a museum that display’s Henri Labrouste’s architectural tools in such a loving way, decide to demolish its next door architectural gem?

In one of my monthly trips to New York City in March, I was delighted to be able to fit in a visit to see the recently opened Labrouste exhibition which has received only rave reviews for both its content and the exhibit’s design. The fantastic drawings and models, the way they are displayed and the story told about Labrouste’s Parisian libraries, is a celebration of architecture for architects. It literally took my breath away and was one of those experiences in which I muttered, “I’m not worthy, I’m not worthy” at the same time being so proud to be an architect. The book of the same name is profound scholarship itself, written by the joint directors and their curators at Paris’ architecture museum, the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine and MOMA. Having visited the Cité de l’Architecture last year, marveling over floors of models and salvaged architectural elements, it is a joy to see its impact here.

Trading In Art for Real Estate

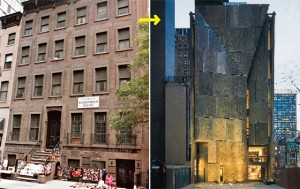

The American Folk Art Museum was opened in 2001 on the former site of two west side brownstones. Photo courtesy NY Magazine.

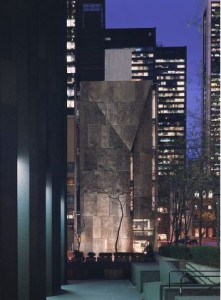

Which brings us to the American Folk Art Museum. The tale of this museum is a cautionary one for all institutions not to overextend themselves. The museum was established in 1961 and opened its doors to the public for the first time on September 27, 1963, in the rented parlor floor of a townhouse at 49 West 53rd Street. In 1979, the museum purchased two townhouses adjacent to 49 West 53rd Street, just west of MOMA. It rented space until its building, designed by Todd Williams Billie Tsien Architects opened in 2001. The façade of the 85-foot tall building is clad in sixty-three textured panels of a lustrous white bronze alloy known as Tombasil. The material—used here for the first time architecturally—is faceted in three large planes that evoke the human hand and catch the light at different angles. A large skylight crowns a ceiling-to-floor open core, sending natural light through the entire height of the building. It displayed 500 pieces of the 5,000 piece collection. I only visited the museum once but it was a giddy experience with another modernist friend, a distinct difference from the bombast of its neighbor’s art mall.

Todd Williams Billie Tsien Architects designed the luminous Folk Art Museum adjacent to the Museum of Modern Art. Copyright Michael Moran for Arch Daily.

The American Folk Art Museum board had taken on $32 million in debt to finance the museum and then defaulted on that in 2009. MOMA purchased the site in 2011 for $31.2 million, announcing earlier this month its demolition plans to make way for more gallery space that is more in keeping aesthetically with its white steel and glass. And the floors of the little museum that could won’t line up with its lofty floor heights. Their announcement has met with universal derision. Paul Goldberger’s piece on it for Vanity Fair is a good and irate read.There are so many reasons to keep this building, all of which MOMA could easily embrace. It could be used to display its own architecture and design collection. It could be an educational center. It could even be another money-making restaurant or shopping venture (my least favorite choice.) It could be MOMA’s example of adaptive use and as such could become its own sustainability think tank. They could ask its designers to help them remake it.

Glenn Lowry, the museum’s director, paid Todd Williams and Billie Tsien a visit at their offices to inform them of the board’s decision. Did any of the board accompany him? No! Todd and Billie’s statement on their website is heartbreaking. The Folk Art Building stands as an example of a modest and purposefully conceived and crafted space for art and the public: a building type that is all too rare in a city often defined by bigness and impersonality. We remain enormously proud of it, and are deeply saddened that a significant building that was a source of enjoyment and inspiration for so many will now be lost forever.

What a class act. I served on an arts panel with Billie in the mid 1990s and have crossed paths with them at Columbia alumni events. I have always been impressed by the modest demeanors of these design giants.

A view of the galleries in Paris’ Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, the co-curators of the Henri Labrouste Exhibition.

I’ve been thinking about our landmarks laws in regards to this sad situation and acknowledge that our protection of landmarks by age is so limited. We save good background buildings that are over 50 years old and are encouraged to use rehabilitation investment tax credits on their reuse. But for this building, a landmark and icon before it was even built, we have no way to protect it from a real estate and money-hungry museum monster, other than in the court of public opinion.

Can Anything Save The Folk Art Museum?

There is no code or landmark ordinance today that can protect the Folk Art Museum. The only thing that will save it is if MOMA reverses its decision and does what’s right. Is that too much to ask of one of America’s creators and defenders of modern beauty and innovation?

Two Years & Counting

As a celebration of my firm’s two-year anniversary I will be posting each day this week about places I’ve visited in the past year. New York City is the great city love of my life, so to have to share this story about the American Folk Art Museum is particularly hard. We can only hope that the cultural powerhouses who are calling for MOMA to rethink their announcement will have some impact.

And if you’d like to “subscribe” or follow my blog, True Green Cities, please sign up through the “Subscribe” button at the bottom left of this page. You’ll receive a daily recap when new blogs are posted. Or Sign up for the Feed.