Architects like me often forget that true sustainability has three sides to it: environment, economy and equity. As a tactile person, I get the environment and maybe even economy, but equity (or equality) is harder for me to understand. Earlier this winter, I visited a site that had all three, with “equity” being possibly the bigger “e”, which so rarely happens.

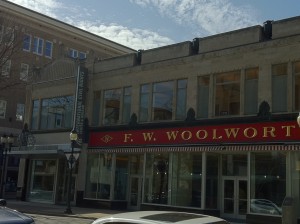

How Does A Woolworth’s Become the Site of the International Civil Rights Museum?

Two years ago a nice downtown Greensboro, NC building, which had been the local Woolworth’s, opened its doors as the new International Civil Rights Museum. In 1960 four freshmen from local A&T University started a sit-in at the lunch counter at Woolworth’s, which transformed this country. The “Greensboro Four” as they came to be called, felt that they needed to step up, or sit down, for what they believed – that everyone, no matter what race or color, should be able to eat lunch at the same lunch counter anytime they wanted. At that time, African Americans could buy lunch there, but only as take out. They could shop in the store but they couldn’t eat in the store. As someone who was born after 1960 and doesn’t remember any of this, it’s really hard to believe.

Interpreting Equality

It’s a small museum, with a guided walk through the exhibits, which begin in the basement. But it is very well done, leading visitors through a timeline of key civil rights actions, including a room of horror which was difficult to walk through, to set the stage for why a sit-in at a lunch counter in a mid-size North Carolina city had the ability to transform the landscape. The museum was designed by the Freelon Group of Durham, N.C., and its exhibitions were designed by Eisterhold Associates of Kansas City, Mo. A New York Times review published the week before its opening, provides a thoughtful examination of the exhibit and building. I suggest you read it for more detail. One sentence from the article resonated with me and captured the emotion of the museum: “One purpose of the museum is to remind the visitor just what was at stake in the seemingly innocuous act of approaching the lunch counter. It celebrates that protest while also resurrecting for the visitor the full scope of the Jim Crow laws against which the movement rebelled.”

A Lunch Counter Is More Than a Lunch Counter

As a historic site professional, what was most interesting to me was observing the other visitors on our tour. Entering the room with the lunch counter was a show stopper for everyone. And everyone kept saying, “This is the real lunch counter. This is where it happened.” (Actually, 8 feet were removed for display at the new Smithsonian African American Museum, also designed by the Freelon Group, so that piece has been reconstructed but is not noticeable.) The tour guide was speaking while we were in the space but I don’t remember any of what she said. All I could think of was how brave and strong the four students were who decided to say no to racism and yes to equality. And that’s what I took away from our visit. If a museum can make you feel one thing so clearly and strongly, then it has done its job. And when the authenticity of a lunch counter is what makes that feeling palpable, then the retelling of the historic action has done its job too. Edward Rothstein declared in the NY Times that a “taste of justified bitterness runs through it” but what I felt was that a tale of justice, strength and fairness ran through it.

And if you’d like to “subscribe” or follow this blog, True Green Cities, please sign up through the “Subscribe” button at the bottom left of this page. You’ll receive a daily recap when new blogs are posted.