I’m teaching a class on the history of sustainable design for a new master’s program at FIT (Fashion Institute of Technology) in New York City. I was intrigued by the topic (Survey of Sustainable Architecture and Interior Design Historical Origins) and the opportunity to dig deeper into this topic, which has so much to do with my professional practice, not to mention the chance to visit my former hometown of NYC for seven weeks in a row. I’ve had a lot of fun creating the syllabus, choosing the readings and doing the readings – when you’re a practitioner it can be hard to find the time for rigorous academic intellectual pursuit, so teaching this class has been a great help in that regard. The course is a mixture of readings, lectures, critical inquiry and site visits around the great metropolis of New York. This is the first of a summary of some of the lectures.

Is There A History of Sustainable Design?

Is it native and indigenous? Or is it just the history of architecture? But isn’t the accepted history of architecture just about monuments? The history of sustainable architecture is about the silent history of technology. Reyner Banham in “Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment”, one of the required texts for the course proclaims, “Services in buildings that provide comfort and well-being of humans should always have been taught as part of the history of architecture.” But rarely are they.

The history of sustainable architecture is also about the silent history of climate and religion. James Steele in his book “Ecological Architecture: A Critical History”, another of the three required texts replies with “Ecological Design is… Accumulated knowledge of past generations in relation to effective ways of dealing with the environment and place.” The history of sustainable architecture can also be about the silent history of native materials and traditions. And Lisa Heschong, in her brilliant treatise “Thermal Delight in Architecture”, the third required text shares that “Buildings are a way to modify a landscape to create more favorable microclimates.”

Is the history of sustainability different from the history of sustainable design? The recent history of high performance or green building design stems from Earth Day, the Energy Crisis and “An Inconvenient Truth.” How does sustainability policy impact design? Architecture and technology should not be separated for one thing. But for most of us it’s easier to understand structure than systems so technology that moderates the environment is handed over to engineers and rarely thought about again.

Are Architects the problem with Telling a More Holistic Architectural History?

Richard Rogers & Renzo Piano’s Centre Pompidou in Paris represents the rare building whose systems have a “gross monumental impact” on their design and hence are shown in the design drawings.

Do we just show the pretty parts of our buildings? What do architects and designers historically show in their drawings? Chimneys and fireplaces seem to be the “systems” most consistently shown. Jefferson showed his “systems” in his drawings for Monticello. Frank Lloyd Wright designed around the hearth in his prairie houses. But typically, only when systems have a “gross monumental impact” on the building are they drawn as part of the architecture documents. Think of Wright’s Larkin Administration Building, Kahn’s Richards Medical Center at University of Pennsylvania and Rogers & Piano’s Centre Pompidou in Paris.

The Energy Crisis – Designers Begin Calling for A Simpler Time

Controlling the environment goes back as far as the cave and the fire. The campfire has become an archetype for warmth. Why were our early structures built? To: Keep dry in the rain. Keep warm in the winter. Stay cool in the summer. And still enjoy acoustic and visual privacy. Most cultures have relied on construction of massive buildings to achieve these goals. Most western architecture is descended from the Mediterranean tradition, using thermal mass and building orientation to moderate the environment. Life exists within a small range of temperatures – and according to Heschong, the hearth and Islamic garden represent the most perfect thermal controls if not the most efficient.

We think we can control the environment now, but have we really mastered it? Vernacular building traditions display sophisticated thermal adaptation. Think of the igloo and its clever use of the insulating value of snow. Or the typical Tunisian house, where families move from floor to floor in different seasons and different times of the day to make use of the thermal mass of their homes.

Has the history of sustainable design been formulated by traditions, technology and urbanism? Traditionally, the discovery of fire brought people together. For millennia, everything we did was embodied in ritual that imposed a predictable pattern on the predictability of nature.

Technologically, the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East and the Nile represents the earliest intertwining of materials, climate and technology. And industrialization created cities of such density that municipal policy was created for the first time to protect health, create municipal water systems and manage sanitation. By the year 2000 nearly half of the world’s population lived in cities. The rural to urban transition of the Industrial Revolution was the greatest migration in human history.

The Green Movement began to emerge in the 1980s. The French Green Party is one of the first times “green” was used to reference the environment. The UN Brundtlandt commission created the definition of sustainable development in 1987. (Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.) And the European Commission’s “Green Paper on the Urban Environment”, 1990, was the first of many international policy papers.

Tradition, Technology & Urbanism

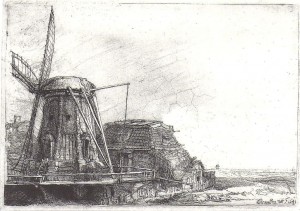

Let’s not forget our traditional technology. A Dutch windmill sketched by Rembrandt in 1641. Courtesy the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam.

Where established practices had time to develop independently, they were perfected in terms of materials used, tools developed, procedures of assembly – and recognized by a whole community. John Fitchen in his masterful book, “Building Construction Before Mechanization”, tells us that significant breakthroughs in building have been mostly gradual and incremental rather than sudden and spectacular. The building industry is historically one of the most conservative of industries, the least subject to progressive practices and now we find ourselves speeding into high performance design in less than a decade. In our new green world, have we taken new technology too far, trying to achieve the spectacular too quickly? Have we forgotten all we’ve learned over the millennia? Let’s not forget the history of our buildings and our technology as we move forward.

And if you’d like to “subscribe” or follow this blog, True Green Cities, please sign up through the “Subscribe” button at the bottom left of this page. You’ll receive a daily recap when new blogs are posted.